Here’s the TL;DR version of this post:

- If you hire or manage writers, learn to be a really good editor. Or hire a professional editor to help you get the very best from your writers.

If you’re doing content marketing of any kind, someone on your team will be reviewing content and making sure it’s good enough to publish.

That person — whatever their title — is an editor.

In this article, we’ll describe the “Collier Marketing” process for writing and editing.

As you’ll read, we use a collaborative process run by our rockstar editor — Katie Stephan — who works closely with me and our friend (and fellow writer) E. Jera Brown on every piece of content we create for clients.

I’ve asked Katie to put together her best tactics for working with writers, which you’ll find below.

She’s a tremendous help to me. I know she’ll be a tremendous help to you too.

If you’re trying to get the best possible work out of your writers (without losing your mind), this article is for you. 🙂

Here’s Katie…

Editing at Collier Marketing

I wear a lot of different hats as the editor at Collier Marketing.

One of those hats is to clean up the work Nathan has done on his own. This may be as simple as catching typos and changing his vast array of em dashes into various other appropriate punctuation.

One of those hats may be to help Nathan brainstorm where a piece is going before he even begins writing. This can involve me being present during a subject interview, reviewing a potential outline before any content is written, or looking at a half-finished piece and helping Nathan figure out where the second half of the piece should land.

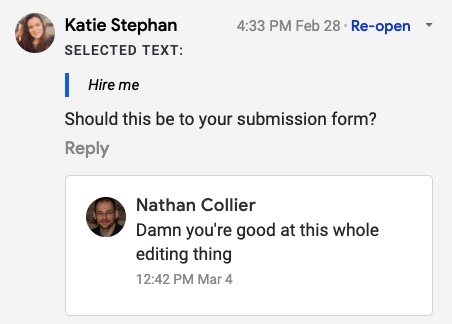

And one of those hats just looks like this:

Because even Nathan needs a little nudge sometimes. 🙂

What Great Editors Do

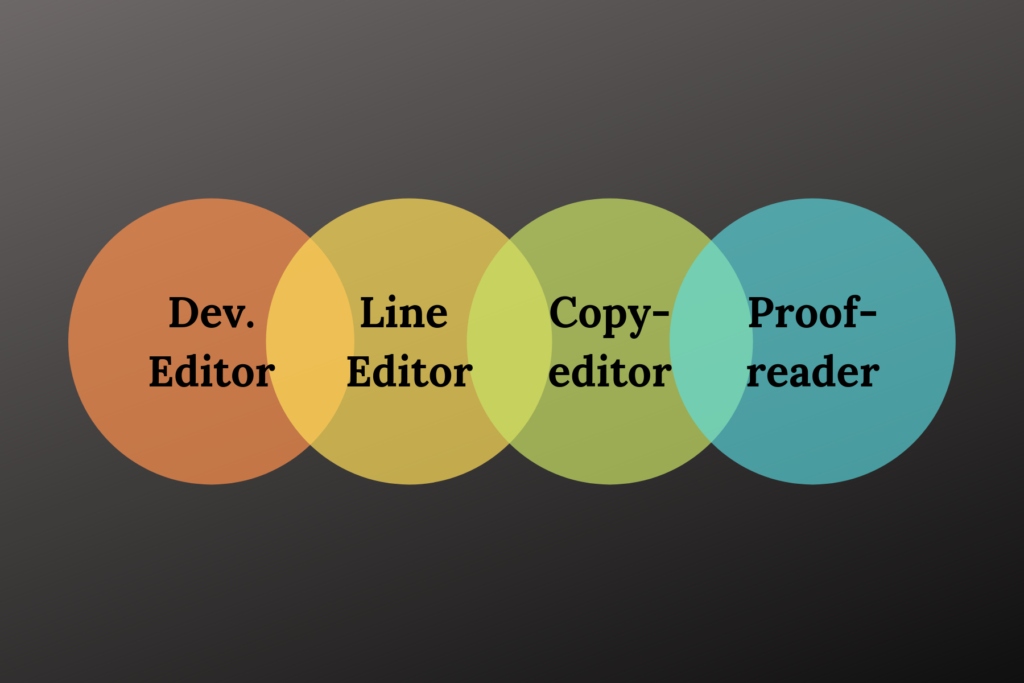

First of all, there are many different types of editors, so we’re going to refer to the Editorial Freelancer Association’s page on Member Skills as a decent standard for explaining the differences.

In a nutshell, know that editors fall on a spectrum, somewhere between proofreaders on one end, and developmental editors on the other end.

Here’s a quick rundown of four common types of editors, according to the EFA.

1. Developmental editors

A developmental editor is present with the project from the very beginning to the very end. They can influence where the writer is going with the piece before it even gets started.

2. Line editors

Line editors can make heavy edits such as reorganization, but they’re probably working with what is already there without influencing the content too much.

3. Copyeditors

Copyeditors are similar to proofreaders, but with different responsibilities: They check spelling, grammar, punctuation, and style. (The EFA states that the Copyeditors may also “check cross-references,” which in the online content world may include checking hyperlinks — but it’s also possible that job may fall to proofreaders or whoever uploads the copy to your CMS.)

4. Proofreaders

Proofreaders generally only look for glaring errors and check page setup.

Making Sense of the Differences

You may have noticed I used a few indefinite qualifiers in the above explanations, including “probably” and “generally.”

If the lines between these types of editors seem blurry, I wholeheartedly agree — the whole thing seems more like a 4-piece Venn diagram of caterpillar shape than a line with clear delineations between roles.

Unless you’re working at a large agency or publishing house where each of these roles is actually very clearly defined, that’s okay.

For instance, I have a “proofreading” client for whom I’m actually doing copyediting and proofreading as a final pass before they publish their pieces. But when they need me to take a pass over the piece, they just say, “Hey, can you proofread this,” not, “Hey, can you copyedit and proofread this?”

It’s semantics, but we understand each other, because we’ve discussed what they actually want me to do on the piece.

And that’s what’s really important — not the label, but that the editor is providing what the client or writer needs, regardless of what everyone decides to call the role.

It’s very important that the editor is getting paid correctly for their efforts — this is where the labels can come in handy.

If the client is trying to pay proofreading rates to an editor doing developmental editing, labels can become very handy very quickly for referring to industry standard rates for compensation.

For my “proofreading” client for whom I also do copyediting, we have a pre-negotiated flat rate per piece I check, so the hourly rate isn’t as important. Both sides are happy with the setup.

Having a Collaborative Relationship

When I edit pieces for Nathan, I usually function as all of the above.

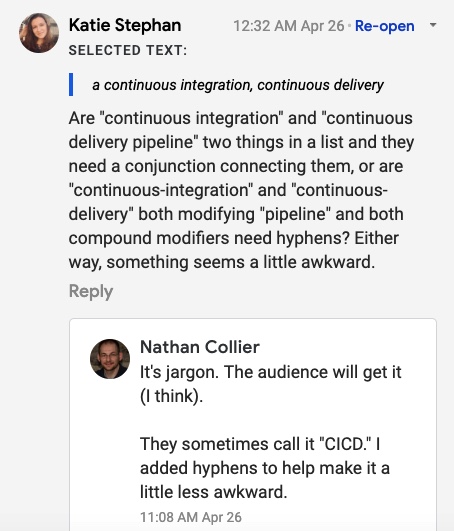

If he wants feedback on the direction of a piece in the early stages, I give him feedback as a developmental editor. This usually includes using a lot of comment functionality to give commentary or ask questions about writer intent for any words, phrases, or passages where I may have been confused as a reader.

It may also involve an actual conversation, either in person or on the phone to brainstorm or discuss the nuances and goals of a piece.

I might see that piece a second or third time as a dev editor, as he makes tweaks and then asks whether his updates have answered my questions. Then, after the content has settled, I’ll take one last pass as a copyeditor and proofreader to make sure nothing sounds odd and nothing is misspelled.

This last pass is also when I try to weed out repetitive punctuation or phrases.

Nathan uses many ellipses in a rough draft, but most of those get removed by him before a piece hits the proofreading stage.

He also loves using em dashes and would leave all of them in even through a piece getting published; I might change a few to commas or parentheses for preciseness or variety.

Regarding labels, Nathan often calls this last pass “line editing,” while I think of it more as “proofreading,” and according to the EFA, it’s probably more accurately “copyediting.”

Again: All that matters is that both the writer and editor know what needs to be accomplished and have agreed upon a price for that service.

Collaboration Tricks

One of the reasons Nathan appreciates my editing is because I try to read the piece as any objective reader would.

This requires turning off the subjective part of my brain that says “We like Nathan and we think he’s really smart” and turning on the objective part of my brain that says “This is just another piece by just another writer — is it any good?”

And one of the ways we facilitate collaborative editing is to make the process a dialogue.

We often do this using Google Docs’ Comments functionality (or in Microsoft Word, Notes).

Editing as a Dialogue

I recently left a full-time corporate editing job. I left for a variety of reasons, but one of the reasons I particularly don’t miss the job was the almost complete absence of dialogue between the writers and editors.

In that particular organization, the editors were expected to just fix the mistakes the writers made, unless the submission so completely missed the brief that it was worth sending back to the writer for heavy revisions.

My frustration came from the fact that I often worked with the same writers over and over again. But unless they made such weighty mistakes that it was worth sending back to them with fundamental revision notes, they just kept making the same types of mistakes every time they submitted another piece.

There was no dialogue between us in which I could easily tell them how to improve over time.

In a world where editing time is money, fixing the same mistakes over and over again literally costs money.

Dialogue Leads to Discourse

Maybe it’s just because I’m a teacher at heart, and I love when writers learn how to be better writers.

Or, as Nathan has pointed out to me, maybe it’s because I’m also an organizational person at heart, and I want processes and people to be as efficient as possible.

Either way, when I edit, I don’t always just fix a writer’s “mistakes.”

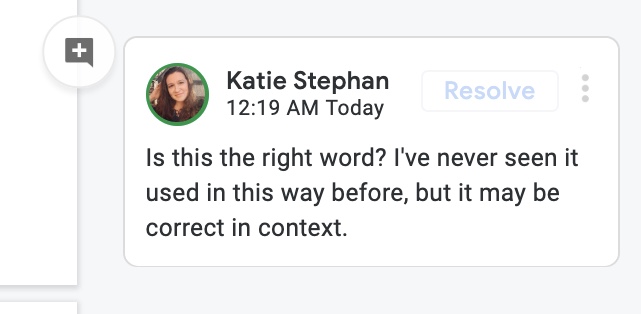

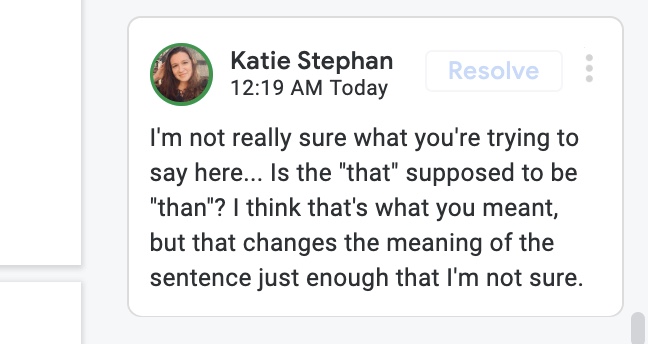

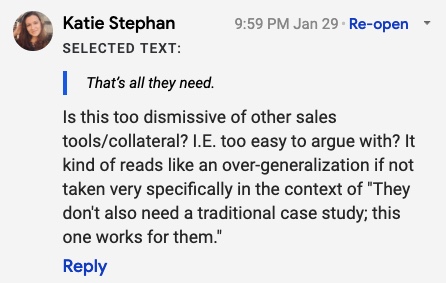

“Mistakes” is in quotes because so much about writing is relative. Some mistakes may be obvious errors, such as misspellings. But others may be much less clear due to style, usage, tone, regional or colloquial norms, or even industry lingo.

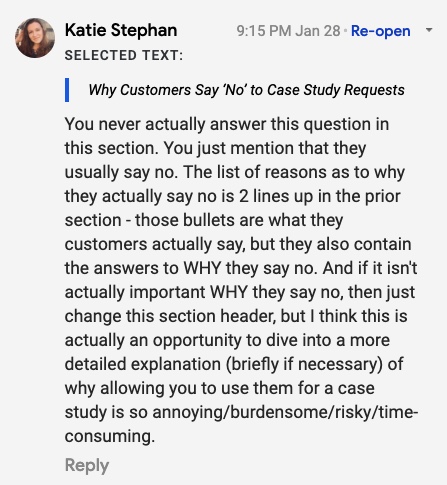

Sometimes, I might not know whether a “mistake” is a true error, so rather than making a change that may not need made in the first place, I ask a question or make a comment:

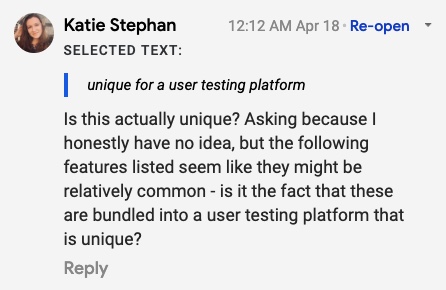

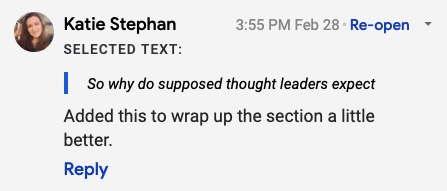

Other times, I might not know what the writer intended exactly — so I can’t make the change. Instead, I start a conversation on the point:

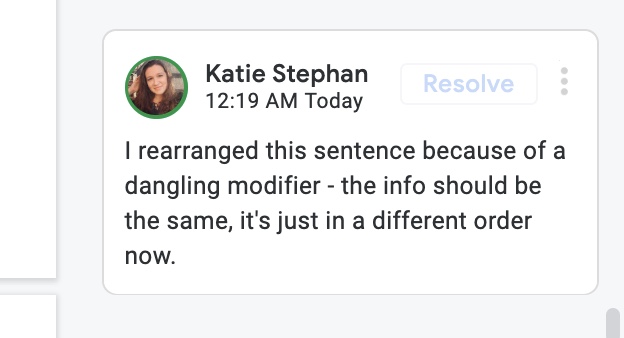

Still other times, the issue may not be as simple as making one small line edit, and I want the writer to know why it appears that I butchered their original content:

Some comments are very specifically developmental, referring to items such as preciseness of language, the development of a concept mentioned in a header, or the order of the sections:

Long-winded though they sometimes are, these are the kinds of comments Nathan loves to get, because they allow him to take a deeper look at his writing and what he wants it to convey to his — or his client’s — readers.

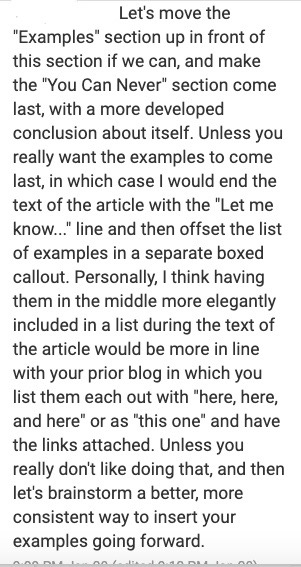

Sometimes, I overthink things and need to clarify as much:

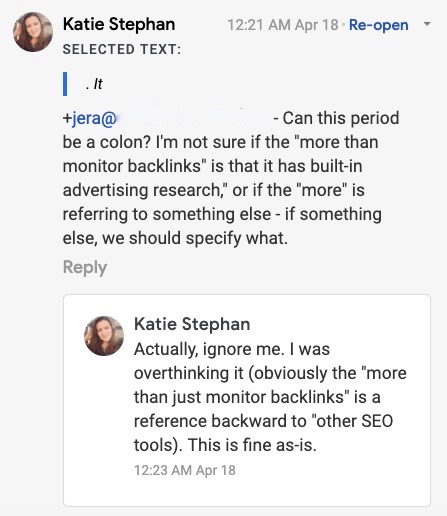

And, to really drive home the editing-as-dialog concept, sometimes writers comment to me preemptively:

Jera knew I was going to see that and think, “Well, it’s usually spelled ‘Sheila;’ now I have to look her up on LinkedIn or the client’s website and see if this is an error or a purposeful deviation.” So she threw a comment on to let me know I didn’t need to do that.

This why building relationships between editors and writers over time is important: It very actionably leads to saving time and money.

Conclusion

Good content is clear, concise, compelling, and correct — and I’m trying to help my editing clients check all of those boxes.

If a writer can better check those boxes because I took the time to give detailed feedback on their piece, they’re going to keep coming back to me for more editing. Because I want to help them create the best content possible.

Next Steps

In case it wasn’t obvious, Collier Marketing can help you create content for your content marketing efforts. If you’d like to talk about working together, you can get in touch here.

We also invite you to join our Facebook group for content marketers (4,000+ members).

If you have questions about writing, editing, or anything content marketing related, drop a comment below. We’d love to hear from you, and we’ll respond to every comment as soon as we can.

Thanks for reading!

If You Want More on This Topic…

We did a podcast on the topic.

Listen to it here or on your podcast player of choice (Search “The Content Marketing Lounge Podcast”).

Or you can listen to the YouTube version here: